Hair Studies: Braids & Dreads

Micro braids, goddess braids, Ghana braids, snake, mohawk, dutch, french, halo, fishtail, waterfall… it seems there are as many types of braids as there are types of hair.

Nearly 5 million braiding videos are available on YouTube, and here in the famous melting pot of New York City, a parade of braided styles can be seen on any day. Braids are highly functional – but their historical roots run eons deep, and tell fascinating social, spiritual, and geopolitical stories.

Where Did Braids Originate?

Africa, considered the cradle of civilization, is also home to the most famous and intricate braids or plaits, but braids have been worn around the world. The oldest record of braids is a carved statuette of unknown origin called the Venus (or Woman) of Willendorf, estimated to have been made 30,000 years ago as a fertility fetish, which features woven hair capping a voluptuous body.

Egypt

Ancient egyptians have a reputation for invention, including paper, toothpaste, calendars, math, and even condoms. And while they may not have invented braiding – combining three strands of material into one – their hairstyles reflected wealth, age and social group. Young girls wore braids or ponytails. Royalty wore braided wigs, as did elders to hide the lack of hair or greyness.

Braids were adorned with berries, petals, linen ribbons, or as a show of status, threaded with gold. Braids were often used as extensions to thicken hair. For men, beards were a symbol of divinity and not worn by the everyman, but those who did braided them in the style of Tutankhamun’s gold burial mask. Queen Meryet-Amun was entombed with extra braids for a stylish afterlife.

Braids were a sign of wealth and the leisure it affords; the more elaborate, the better.

Greece

A bust of a Roman woman from the Flavian era

To differentiate themselves from Egyptians, classical Greek women grew hair much longer, and pulled it back into chignons. Many styles involved braids fixed to the head and decorated with flowers, headbands, ribbons and pieces of metal. Braids were a sign of wealth and the leisure it affords; the more elaborate, the better.

Italy

During the reign of the Emperor Augustus, detailed hairstyles came into fashion as an expression of wealth and status. False hair pieces made hair thicker and longer. Sophisticated braids and knots were adorned with pearls and jewelled pins.

Americas

In Native American tradition, hair is a signifier of one’s spiritual practice. Combing represents the alignment of thought; braiding is the Oneness of thought, and tieing is the securing of thought. Flowing strands of hair are considered individually weak, but when joined in braids they demonstrate strength in unity. Letting hair flow free demonstrates harmony with the flow of life, and braiding indicates thoughts of oneness.

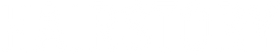

Inuit woman, Nowadluk, with long hair

Chief Gall's granddaughter wearing braids adorned with shells

China

For centuries, the Manchu dynasty forced people to wear hairstyles prescribed by rank, and rice farmers wore braids down the back. When Yat-sen, the chinese leader of the late 20th century overthrew the Manchu dynasty to bring people out of feudalism, he encouraged braid-cutting, which became common in urban areas; but braids were so deeply rooted in rural tradition that murder and suicide were committed in their defense.

The queue worn by Manchus of Manchuria

...braids were so deeply rooted in rural tradition that murder and suicide were committed in their defense.

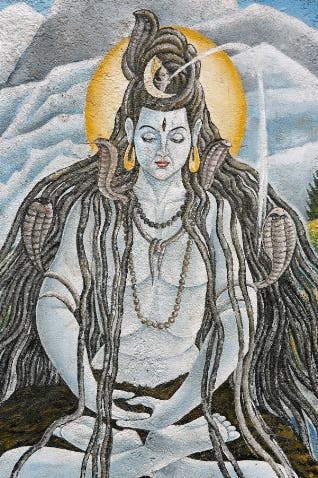

Africa

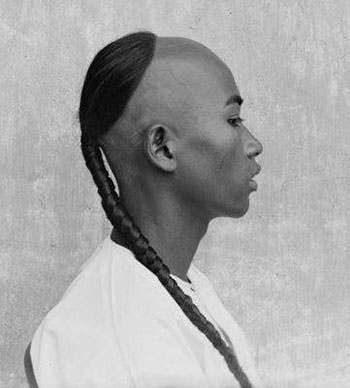

Arguably, the richest hair traditions have been sustained – some might say reborn – from their origins in Africa. Tribal cultures endowed hair with spiritual significance and immense power. As the most elevated part of the body, hair was believed to be the conduit for gods and spirits to reach the soul. Hairdressers were trustworthy members of society, senior women, family or close friends with whom tribal bonds could be cemented, and grooming rituals often lasted several hours, even several days.

Arguably, the richest hair traditions have been sustained – some might say reborn – from their origins in Africa. Tribal cultures endowed hair with spiritual significance and immense power. As the most elevated part of the body, hair was believed to be the conduit for gods and spirits to reach the soul. Hairdressers were trustworthy members of society, senior women, family or close friends with whom tribal bonds could be cemented, and grooming rituals often lasted several hours, even several days.

As the most elevated part of the body, hair was believed to be the conduit for gods and spirits to reach the soul.

Twisting, braiding, beading, and grooming also forged meaningful bonds between elders and children, and traditional techniques were thus passed along generations. Braiding customs were both ritual and social service, but requiring no reward or pay; it was in fact unlucky to offer thanks.

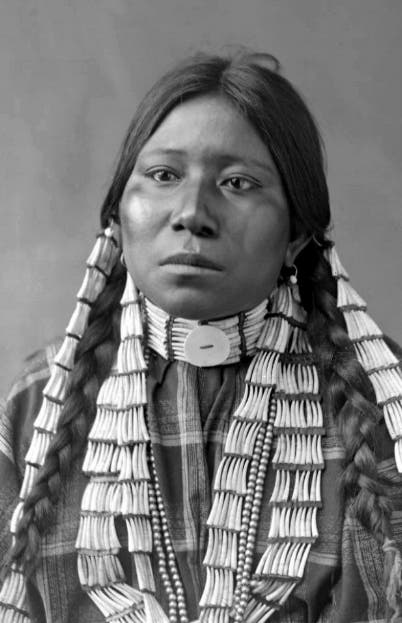

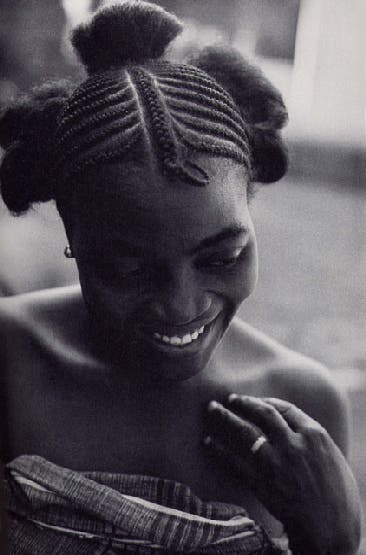

A Mende style, 1970; photo by Rebecca Busselle

Loose hair can indicate a lack of hygiene and tidiness, while being groomed shows good health and manners; ceremonies for the dead are the only acceptable time to let hair loose. Practically speaking, fire and fire dances are typically a part of social rites, and braiding hair keeps it safer from open flame.

Details vary from tribe to tribe: Mangbetu women plait hair and arrange hair in cone-shaped basket frames decorated with bone needles. Miango women decorate braids with scarves and leaves. Massai men stiffen them with animal dung, and Himba women mix red ochre, butter, ash and herbs to coat them; a girl is entitled to only two braids, and acquires more once she marries. Himba men wear one braid, and tie it into a turban after marriage. Mbalantu women put finely grounded tree bark and oil into their hair starting at the age of 12 to help it grow long and thick, and braid it into elaborate headdresses throughout their lives.

A girl of the Himba tribe

A Dan style from Côte d’Ivoire, 1939

Common African tribal beliefs include: Hair should be cut on a full moon for it to grow longer; twopeople braiding a person’s hair at the same time could result in the death of one groomer; pregnant women should not braid others’ hair; hair should not be combed or braided in the open.

Twisting, braiding, beading, and grooming also forged meaningful bonds between elders and children, and traditional techniques were thus passed along generations.

History of Dreads

Telling a very different story are dreadlocks, or “nature’s braids.” When hair is left ungroomed long enough – and coaxed into form by hand with various unguents – it will naturally knot into rope.

Ethiopian Emperor Ras Tafari

Theories on the origin of the term dreadlocks vary, but most agree that a socio-religious movement founded by Marcus Garvey in Harlem in the early 20th century attracted an enthusiastic following amongst Black Jamaicans. Based on the Bible, African tribal culture, and Hinduism that had recently taken hold in the West Indies, Garvey promoted the return of the African diaspora to ancestral lands – and abhorred the chemical relaxing of hair, saying, “Remove the kinks from your mind, not your hair.”

Bob Marley

“Remove the kinks from your mind, not your hair.”

The followers of this movement grew matted locks of hair, and called themselves Dreads, signifying that they dreaded, or respected God. Turning their focus on the Ethiopian Emperor Ras Tafari, Haile Selassie, they thus became known as Rastafarians. Selassie was crowned emperor of Ethiopia in 1930, but was forced into exile in 1936 after leading the resistance against the Italian invasion.

Some say that sympathetic guerilla warriors vowed not to cut their hair until Selassie’s release; it became long and matted, and because they were widely feared or dreaded, the term ‘dreadlocks’ was coined. Others say Rastafarians believed Selassie was a biblically sanctioned God – even the second coming of Christ – and as the Bible describes the return of Jesus as the Lion of Judah, dreadlocks were a symbol of the lion’s mane.

Though the term is local, the phenomenon is global – though it should be said that as human history began in Africa it stands to reason that the locking of human hair has origins there as well. The first archaeological record is Egyptian, where ancient mummies have been discovered with dreads still intact. Ancient pharaohs wore them as seen in tomb carvings, drawings and other artifacts.

The first archaeological record is Egyptian, where ancient mummies have been discovered with dreads still intact. Ancient pharaohs wore them as seen in tomb carvings, drawings and other artifacts.

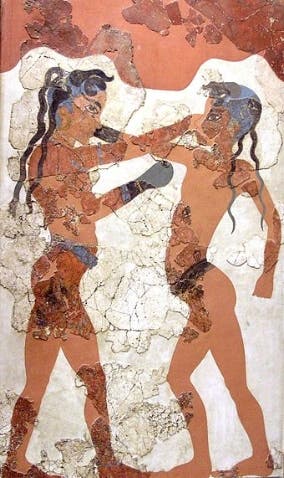

Dreads were worn by Romans in the celtic era, Vikings, germanic tribes, monks in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Nazarites of Judaism, Qalandris, Sufis, Sadhus of Hinduism, Dervishes of Islam, and early Christians. In 2500 BCE, The Vedas, Hinduism’s oldest scriptures, depicted the Shiva wearing locks, or jaTaa in Sanskrit.

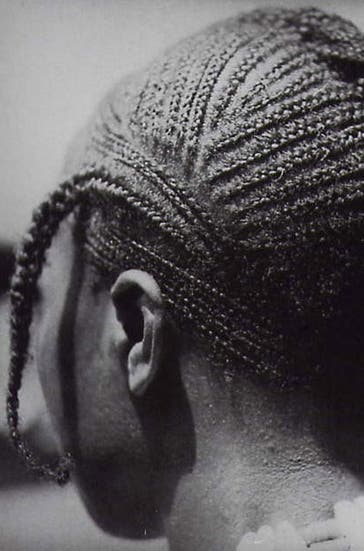

Frescoes in Santorini, Greece made 3600 years ago, and over half of extant ancient Greek Kouros sculptures depict men with dreads. Spartan warriors were shown with them on their battle robes.

Fresco from Akrotiri, 1600–1500 BCE

The Hindu deity Shiva

The first Bishop of Jerusalem, James the Just, was thought to have dreads to his ankles. Yogis, Gyanis and Tapasvis are among famous wearers. In Buddhism, dreads are symbolic of material non-attachment; students in classical India on a spiritual path grew them to detach from physical vanity and to develop mental and spiritual powers.

Photo by Joseph Lawrence, from his Holy Men series.

Many traditions teach that the top of the head – the crown chakra as it is most widely known – is the portal for physical, mental and spiritual energies.

Many traditions teach that the top of the head – the crown chakra as it is most widely known – is the portal for physical, mental and spiritual energies. If hair is uncut, and knotted, it can store energy within the body to maintain strength and health, or as Rastafarians say, hair is our “God antennae.”

Dreadlocks: Spiritual intent, supernatural power, non-violence, non-conformity, communalism, socialism, solidarity... that is the power of hair.